It has been a while since I published Issue #8. Issue #9 required a lot more research than previous issues. I kept digging deeper on a few things and time just slipped past. You may recall that as Issue #8 concluded, Joni and I were about to settle in Nashville. I am happy to report that we found the perfect location.

We had four critical locations to consider as we planned our move to Nashville: Joni’s work location, our place of residence, a grocery store, and a bus stop. It is hard to imagine how we could have done any better than where we ended up living.

I know some of my readers are blind so I will describe for them the image I have included below.

Above is an aerial photo from Google Earth. It shows a small section, less than a square mile, of West Nashville along Harding Road, one of several major thoroughfares that extend from downtown. In the left center of the photo is the Imperial House Apartments. The image date is 2017. I had to add a label for the apartments, since at the time of the photo the owners had prepped the building for demolition. But in the 1980s the Imperial House was up and running. A unit on the 11th floor became our new home. Within easy walking distance (just over an eighth of a mile) was the HG Hill Grocery Store shown near the bottom of the photo, and St. Thomas Hospital, Joni’s new employer, shown at the top. A short walk to Harding Road was all we had to do to catch a bus.

Joni applied to Vanderbilt University Hospital and St. Thomas Hospital. I helped her fill out the paper forms at Vanderbilt’s HR office, so we knew full well why they did not even grant her an interview. I cannot help but to engage in a bit of schadenfreude here. As I was preparing this issue, I stumbled across a most interesting article, one that warrants mention.

Vanderbilt opened a transgender clinic in 2018. Thanks to the work of Matt Walsh, we now know that the driving force, one of the doctors, sold it as “a big money maker” since a lot of “follow up” was required. The clinic offered chemical castration and double mastectomies were available for teenage girls. Hormone treatments were an option for children as young as thirteen. Not everyone was on board with this new iteration of health care, so the doctor issued thinly veiled threats. There would be “consequences” for those who would not toe the line (translation: my way or the highway). When all this became known, in a most revealing reaction, the clinic nuked its own website. I believe the clinic would have continued operations unabated had it not decided to market its services for children.

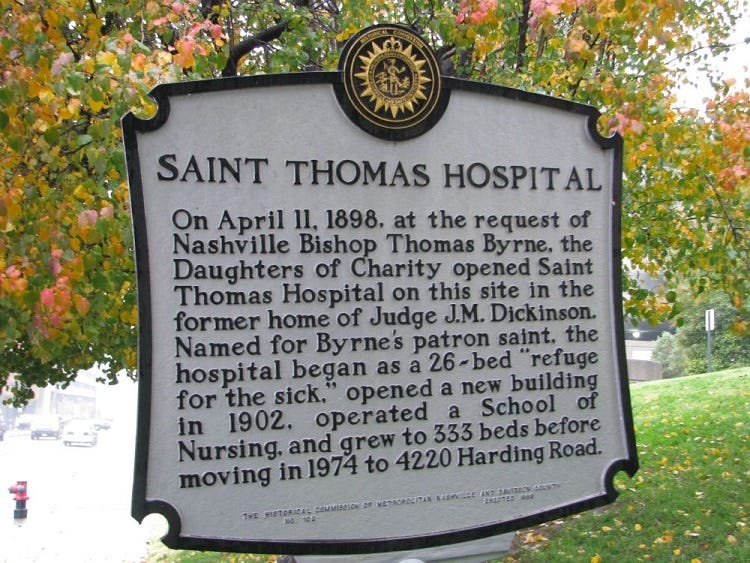

As compared to other hospitals in Nashville, as well as Joni’s previous employers, St. Thomas offered an environment of a different sort. An historical marker located on Hayes Street in Nashville provides a concise history and the defining element that made it unique.

The marker reads as follows:

On April 11,1898, at the request of Nashville Bishop Thomas Byrne, the Daughters of Charity opened Saint Thomas Hospital on this site in the former home of Judge J.M. Dickenson. Named for Byrne’s patron saint, the hospital began a 26-bed “refuge for the sick,” opened a new building in 1902, operated a School of Nursing, and grew to 333 beds before moving in 1974 to 4220 Harding Road.

When Joni joined St. Thomas, the Daughters were active in all departments of hospital operations, and one of the Sisters functioned as the CEO as had been the case for eighty-five years. Whenever I had reason to visit the hospital, one of the Sisters was usually there at the information booth. Something about the atmosphere told me that Joni had found the perfect place. To this day, I marvel at the improbable sequence of events that led her to St. Thomas where she earned the respect and admiration of everyone she encountered.

We stayed at the Imperial House a year or so and during that time, unbeknownst to us, the forces of nature were hard at work beneath the lawns, the fields, and every patch of earth. A vast army in the billions was gathering strength. We were at the Imperial House when those masses of not-so-tiny soldiers rose from the ground to wing their way into the trees where they produced a deafening cacophony of sound. The 17-year cicadas, the most numerous of the fifteen different broods, were back just in time to welcome us to Nashville. As many as one million of them could be found in a single acre.

Male cicadas have sound boxes inside their abdomens. They produce a high-pitched buzzing sound by expanding and contracting a membrane called a tymbal. Those contractions can occur hundreds of times in a mere second, so their distinctive sound, which functions as their mating call, seems continuous to us. The females respond by clicking when they are ready to mate. Some amusing thoughts come to mind and that is where they will remain.

To complete the remarkable story of the cicada, the female lays hundreds of eggs in the tiny holes she makes in the bark of trees. In a matter of weeks, the ant-like hatchlings, called nymphs, drop to the ground where they burrow into the soil to feed on tree roots. Seventeen years later and fully matured they emerge from the ground to begin the cycle again. The 17-year cicada, unlike the various annual broods, lives for only a few months. Soon after arriving in Nashville, their little carcasses began showing up everywhere. I swept dozens upon dozens of carcasses from our balcony on the eleventh floor.

Neither Joni nor I had ever encountered such a phenomenon. This brood of cicada produced sounds that overwhelmed us. We felt like we were living inside a low budget horror movie. It was eerie. Cicadas do not bite. They are harmless to humans, but they do fly and would frequently bump into you or you to them. And sometimes upon your shirt or in your hair they would light. A sort of cicada courtesy soon developed, especially among bus riders. If you were the only one waiting for the bus, there was ample time to garner a few attachments. Those you could see you easily shooed away, and once you boarded the bus a fellow passenger would pluck off the sneaky ones that clung to your back.

Soon after the cicadas disappeared, we purchased a home on Kenner Avenue just over three-quarters of a mile from the grocery store, the hospital, and the bus stop. The walk became routine for us. Joni started using a white cane. I remember that moment vividly. I was waiting for Joni outside the hospital’s main entrance that day. When she appeared along the walkway, I noticed the cane. We both knew it was coming. With our recent move to Kenner Avenue, use of the cane made good sense.

Joni had an early shift at the hospital, so I would often get to walk with her to a point just across Harding Road, then catch the bus in route to one or other of the jobs I held during our years in Nashville. Marilyn, another transcriptionist in the department, worked that same early shift and offered Joni rides home. Neither of us ever asked for rides, but when coworkers offered, we gratefully accepted.

For Joni, there was Marilyn. For me, there were several coworkers who deserve some gratitude from this league bowler: Rob at Associated Publishers Group, Amanda and Catherine at SunTrust Bank and Patricia in the Davidson County Nashville Budget Office. The CEO of Endata even gave me a ride home one time, but I still spent a lot of reading time on the busses.

Our next brush with Nashville history came on Monday, January 21, 1985, when temperatures plummeted to a record -17 degrees, which still stands as the record low. The second coldest temperature of -16 degrees occurred the day before. We had settled into our home on Kenner Avenue by then, so our morning walks to work and the bus stop on Monday and Tuesday that week were invigorating (obviously my choice of adjective). We bundled up like Ralphie’s little brother in the movie “A Christmas Story.” Ralphie described him as looking like a tick about to pop. Joni made it to work simply fine, and I joined the other bundles on the buses and at the transfer center downtown.

We took advantage of a lot of what Nashville offered: the Annual Italian Street Fair, the Nashville Symphony Orchestra, which performed at the July 4th fireworks downtown along the Cumberland River, the easy access to vacation spots we grew to love. New Orleans, a great walking city, and Mackinaw Island in Michigan (bicycles, horses and your own two feet were your only options) were two of our favorites. Joni arranged a hot-air balloon ride that turned into a real adventure. We outdistanced the chase vehicle and ended up landing in someone’s back yard, fortunately, a friendly someone who gave us coffee and breakfast items as we waited for the chase vehicle to arrive.

As for me, the trail of “Bargain City” ended with an agent that took the screenplay nowhere, so it was headfirst into the Nashville work scene, a job sampler’s dream come true. Like a frog in a lily pond, I landed on quite a few of those big green $ pads: accounting teacher, book salesperson, brokerage customer service, loan officer, Davidson County budget analyst to name a few. Only one of those lily pads dumped me into the drink. Layoffs hit Endata Inc., one of the 1980s leveraged buyouts, soon after I arrived. All this by way of saying Joni was our anchor.

1993 was a pivotal year for Joni and St. Thomas Hospital. I will write about that in November. Since I have done most of the research, Issue #10 will not be late.

Thanks for reading Issue #9, and welcome to a new subscriber.